The holy grail of selection is no longer

To hire the top candidate for a job, we require selection procedures that provide a sound assessment of who will perform best. Classic examples of selection procedures include resume screening and job interviews – arguably also the most used selection procedures. But what does the outcome of those procedures tell us about a candidate’s potential? In other words, what predictive value do they have concerning a candidate’s future performance in a given job?

Already in 1998, Frank Schmidt and John Hunter answered these questions. Based on the results from their landmark study, cognitive ability (i.e. general intelligence) measures were considered the holy grail of selection procedures. Cognitive ability tests ranked above all other selection procedures in predicting future job performance. Moreover, only small predictive value increments were expected when combining other procedures with cognitive ability measures.

However, in a very recent re-evaluation of the validity of selection procedures, Paul Sackett, Charlene Zhang, Christopher Berry, and Filip Lievens provide compelling arguments as to why the predictive value of job performance of many procedures is lower than initially thought. In scientific terms, we call this predictive value ‘operational validity’. This re-evaluation includes thousands of studies comprising hundreds of thousands of participants. It comes down to (without getting too technical) that previous validity estimates have been overcorrected. This overcorrection resulted in an overestimation of the predictive value of several procedures.

The landscape of selection procedures is shaken up. The study of Sackett and colleagues sheds new light on the ranking of selection procedures. In what follows, I will give a brief account of these new developments. I can already reveal one thing: the holy grail of selection is no longer.

The strength of structured interviews

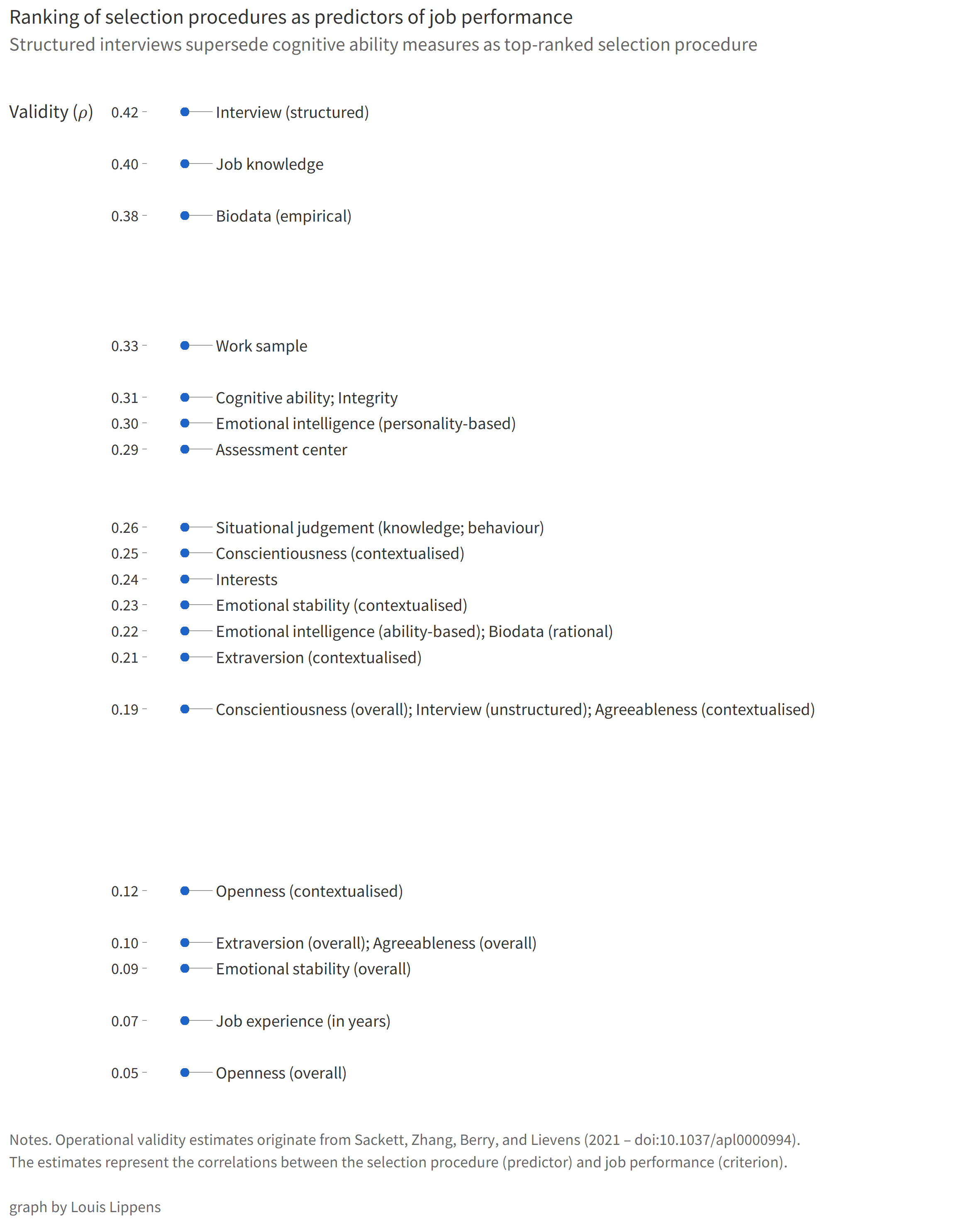

The top five selection procedures are essentially reshuffled. Structured interviews – not unstructured interviews – replace cognitive ability measures as the top-ranked selection procedure. Asking about past behaviour will, in fact, give you information about future behaviour. This new ranking does not mean that cognitive ability measures are no longer relevant or useful – yet it does appear that their predictive value has been substantially overstated.

Structured interviews are followed by job knowledge tests and empirically-keyed biodata (i.e. information related to your working life as well as more personal yet often less relevant and more sensitive details). Work sample tests and, tied for fifth, cognitive ability and integrity tests complete the top. Notice, at the bottom of the ranking, that just counting the years of relevant work experience is barely predictive and thus not a good practice.

Not a one-size-fits-all

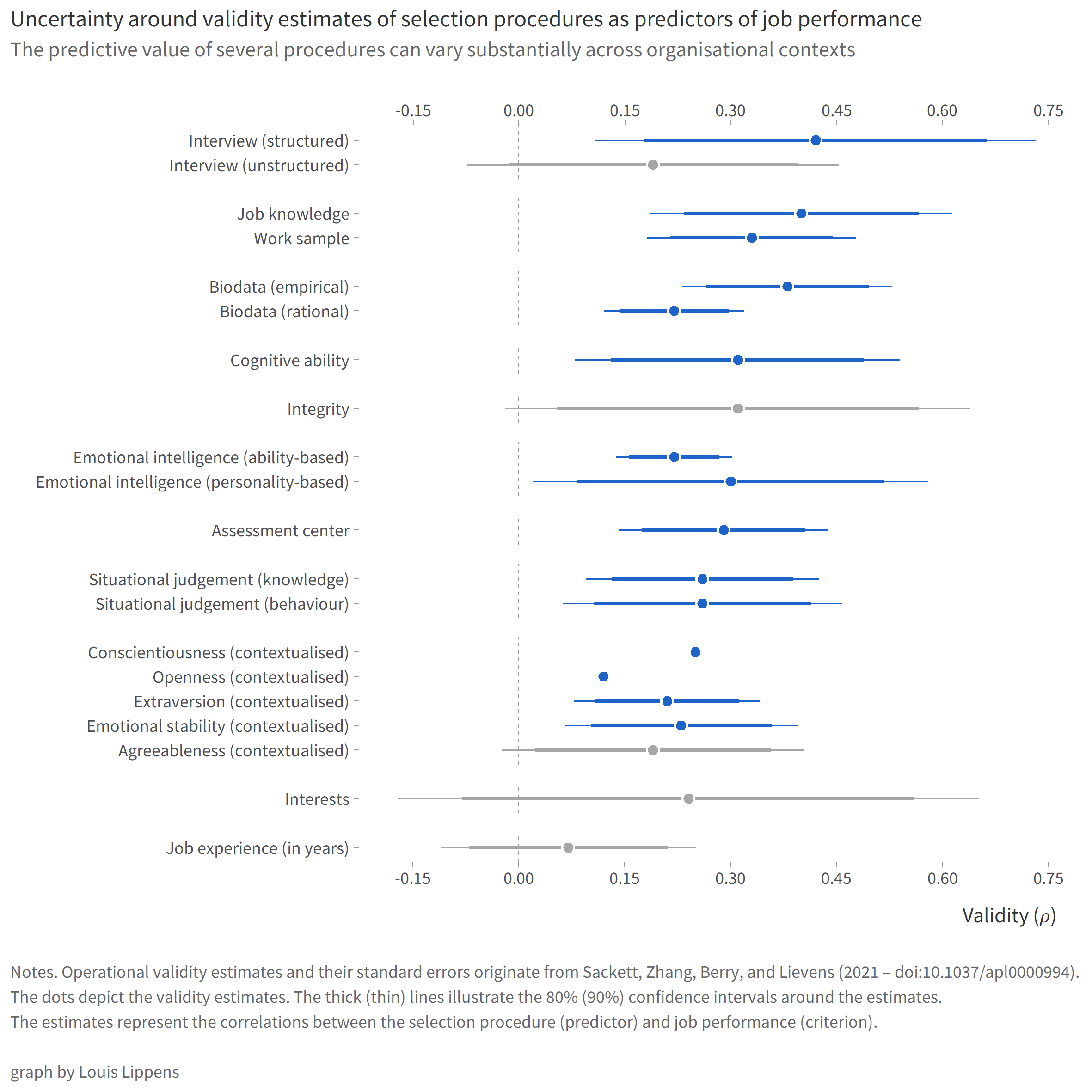

The results seem clear-cut: structured interviews outperform all other selection procedures for predicting job performance. Thus, we should just commit to this ’new holy grail’. Well, in consulting, one would say: “It depends.”. The predictive value of job performance of several selection procedures varies substantially across studies and, hence, across job types and organisational contexts. It is not a one-size-fits-all.

Building further on the example of structured interviews, you probably already asked yourself what such an interview would look like. There is no straightforward answer to this question. A lot depends on, for example, which elements are essential or relevant to the job or the employer, who drafts the interview, or how structured the interview is. There is no such thing as ’the structured interview’.

The issue of applicant diversity

Until this point, I have only written about selection procedures as predictors of job performance. Nevertheless, employers might not just be on the lookout for the ‘unicorn candidate’ that ticks all the boxes but might also want to increase their organisational diversity – team diversity and team performance go hand in hand. The latter statement is especially true for functional and educational backgrounds. Therefore, knowing the potential adverse effects of selection procedures is essential.

Adverse effects arise when a selection procedure consistently disfavours a specific group of applicants, resulting in overall discrimination at the group level. Our recent meta-analysis demonstrates the persistence of discrimination in the resume screening process. This discrimination is not limited to ethnicity but also includes age, disability and physical appearance, among other discrimination grounds. Early exclusion of qualified minority candidates from the application process results in a needless waste of talent.

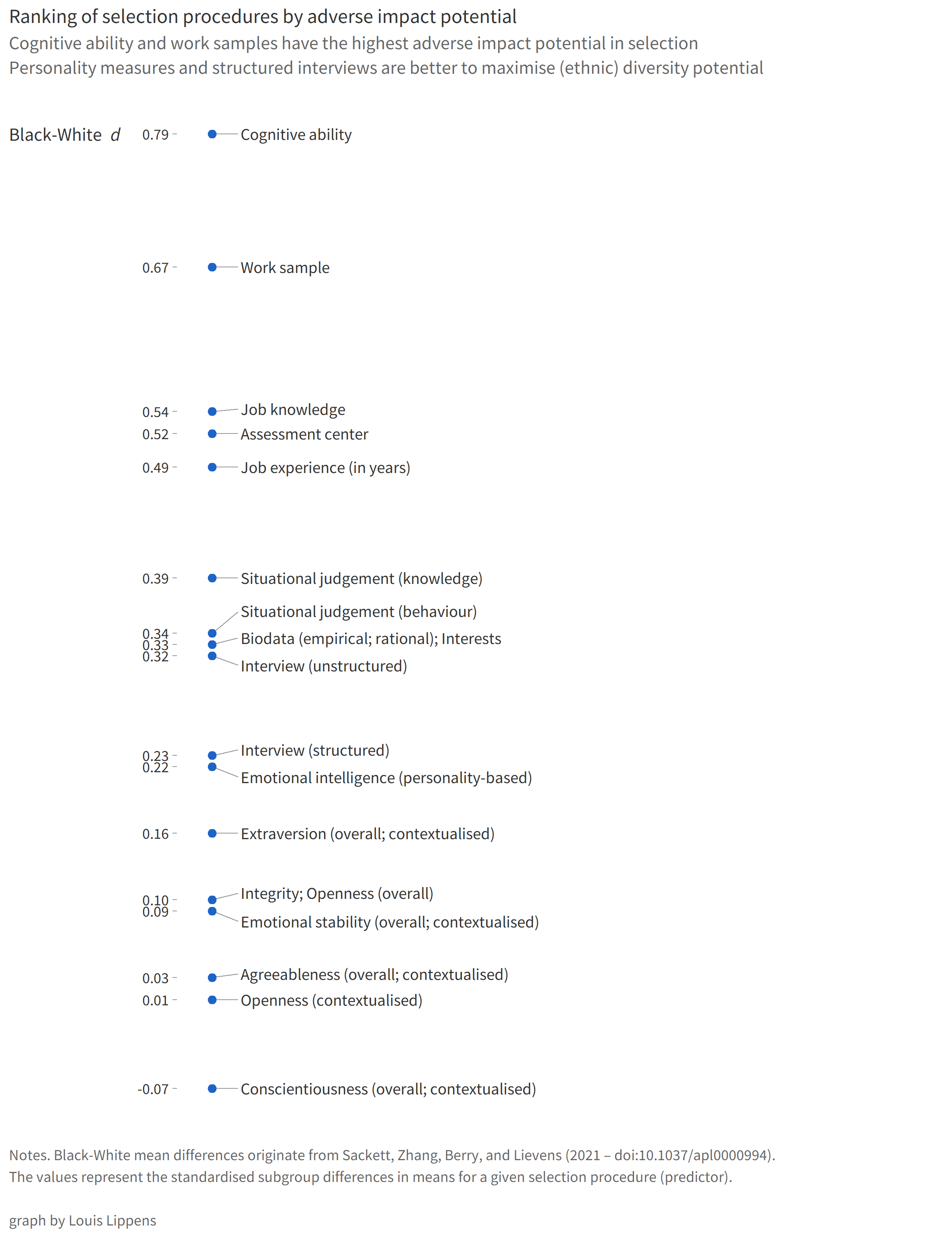

The recent study of Sackett and colleagues also provides information on these adverse effects in the form of standardised mean group differences between Black and White applicants. While cognitive ability measures are no longer top-ranked in terms of operational validity, they are (still) highly susceptible to ethnicity-based adverse effects. These measures are followed by work sample tests, job knowledge tests and assessment centres. Counting the years of relevant work experience completes the top five (although I hope that, by now, you already vouched never to rely solely on this procedure again). At the other end of the spectrum, we have personality measures and… structured interviews.

The best candidate in a diverse organisation

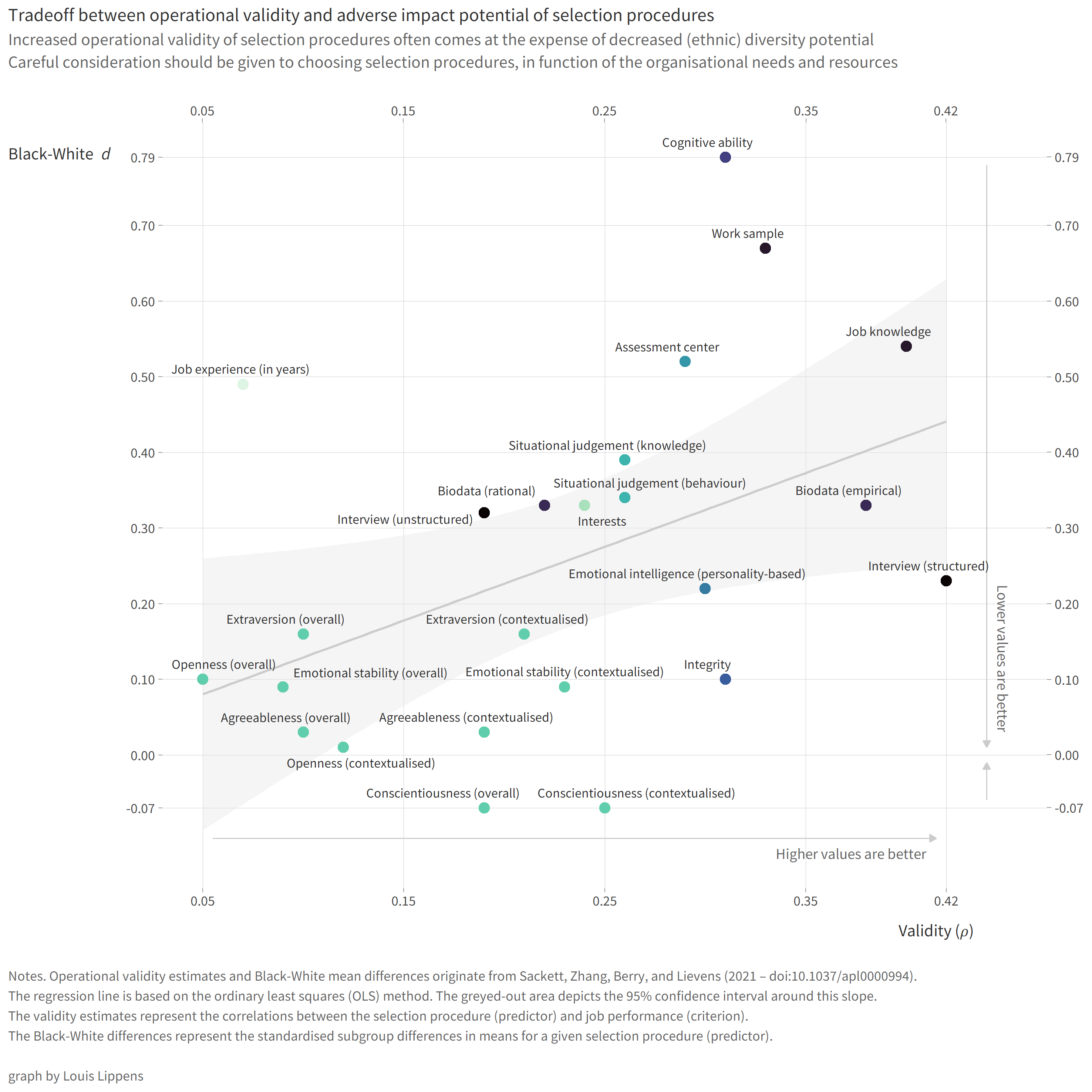

A final takeaway from Sackett and colleagues’ study is that increased predictive value concerning job performance often comes at the expense of decreased (ethnic) diversity potential in selection. This tradeoff is the case for cognitive ability measures, for example. On the other hand, structured interviews, integrity tests, measures of conscientiousness, and personality-based emotional intelligence measures outperform other procedures in terms of validity-diversity tradeoffs.

Using procedures with a high adverse impact potential is not out of the question but does require thorough reflection. As a general rule, when using high adverse impact procedures, try outbalancing their negative effects by also adding low adverse impact procedures to the mix. Specifically, when opting for cognitive ability measures, consider focusing on sufficiently specific and relevant cognitive ability subtests (e.g. language-free) to minimise the adverse effects.

Ultimately, it is up to the employer to determine the most useful selection procedures based on their selection goals, organisational needs, and, of course, the time and resources at hand. Following these new insights, it remains a balancing exercise between selecting the best candidate and selecting a diverse set of candidates. Most probably, the solution lies in using an appropriate combination of selection procedures, maximising operational validity while still cultivating a diverse organisation.

This post also appeared on LinkedIn. Data, code, and key references related to this post can be found in this repository. This page was last updated on 29 November 2023.